Excerpted from Jazz Modernism

Excerpted from Jazz Modernismby Alfred Appel

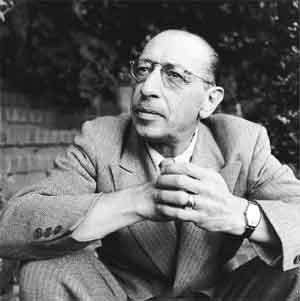

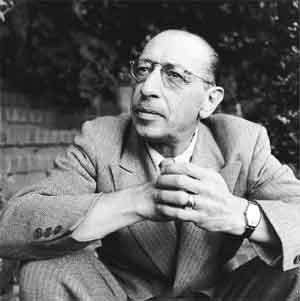

Charlie Parker enthusiasts circa 1950 often declared him the jazz equivalent of Stravinsky and Bartok, and asserted that he'd absorbed their music, though skeptics countered that there was no evidence he was even familiar with it. Parker himself clarified the issue for me one night in the winter of 1951, at New York's premier modern jazz club, Birdland, at Broadway and Fifty-second Street. It was Saturday night, Parker's quintet was the featured attraction, and he was in his prime, it seemed. I had a good table near the front, on the left side of the bandstand, below the piano. The house was almost full, even before the opening set -- Billy Taylor's piano trio -- except for the conspicuous empty table to my right, which bore a RESERVED sign, unusual for Birdland. After the pianist finished his forty-five-minute set, a party of four men and a woman settled in at the table, rather clamorously, three waiters swooping in quickly to take their orders as a ripple of whispers and exclamations ran through Birdland at the sight of one of the men, Igor Stravinsky. He was a celebrity, and an icon to jazz fans because he sanctified modern jazz by composing Ebony Concerto for Woody Herman and his Orchestra (1946) -- a Covarrubias "Impossible Interview" come true.

As Parker's quintet walked onto the bandstand, trumpeter Red Rodney recognized Stravinsky, front and almost center. Rodney leaned over and told Parker, who did not look at Stravinsky. Parker immediately called the first number for his band, and, forgoing the customary greeting to the crowd, was off like a shot. At the sound of the opening notes, played in unison by trumpet and alto, a chill went up and down the back of my neck. They were playing "Koko," which, because of its epochal breakneck tempo -- over three hundred beats per minute on the metronome-- Parker never assayed befor

e his second set, when he was sufficiently warmed up.

Parker's phrases were flying as fluently as ever on this particular daunting "Koko." At the beginning of his second chorus he interpolated the opening of Stravinsky's Firebird Suite as though it had always been there, a perfect fit, and then sailed on with the rest of the number. Stravinsky roared with delight, pounding his glass on the table, the upward arc of

the glass sending its liquor and ice cubes onto the people behind him, who threw up their hands or ducked. The hilarity of the audience didn't distract Parker, who, playing with his eyes wide open and fixed on the middle distance, never once looked at Stravinsky. The loud applause at the conclusion of "Koko" stopped in mid-clap, so to speak, as Parker, again without a word, segued into his gentle version of "All the Things You Are." Stravinsky was visibly moved. Did he know that Parker's 1947 record of the song was issued under the title "Bird of Paradise?"